I’m still waiting to receive the physical copies of All the Quiet Hours. The store is working now if you feel like ordering a copy. The physical paperback is $29.95 and the eBook is $16.95. The book was supposed to be out Dec 21. The delay is my fault because I also had to make a bunch of corrections to the fair copy and by the time I sent off the corrections there was a postal strike. It’s just so much easier to spot errors on the printed page than on a glowing screen. I think our minds are trained to skim past errors if they are made with glowing pixels. Anyway, I had to fix about forty errors in the fair copy and send it back. So depending how long it took to get delivered, physical copies should be ready within a few weeks and then I can start standing on a street corner trying to sell them (if you think I’m joking, you don’t know me very well…I’m gonna busk in front of bookstores until the entire first run is sold).

The best books are books with secrets. Books that don’t behave like books. Books with books inside them. Mysterious books. Not Agatha Christie mysteries (though I do find them entertaining), but books that are mysterious objects of mysterious origin: published anonymously or pseudonymously and whose content baffles scholars, preferably for centuries. I don’t mean bogus shit like Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1903) either. The Protocols purports to document the minutes of a late-19th-century meeting attended by world Jewish leaders who call themselves the “Elders of Zion,” who are conspiring to control the world. The book was assigned mandatory reading in Nazi Germany and continues to be cited by anti-Semites as a genuine document. It’s the most influential work of Semitism ever written.

One early example of the kind of sui generis work I’m talking about is Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), a mysterious Renaissance book whose bizarre linguistic modes, hidden acrostic messages buried at the beginning of each chapter, accretion of increasingly complex puzzles, bogus Egyptian hieroglyphs, and many dead ends sprinkled throughout its pages has vexed scholars throughout history. Originally published anonymously, the book is thought to be the work of an Italian Dominican priest named Francesco Colonna. Colonna was identified through an acrostic formed by the elaborately decorated letters that open each chapter in the original Italian which reads POLIAM FRATER FRANCISCVS COLVMNA PERAMAVIT (translation: “Brother Francesco Colonna has dearly loved Polia.”) Despite the fact that Colonna’s name appears in the text itself, the work has also been attributed to Leon Battista Alberti and Lorenzo de’ Medici, so its authorship is by no means settled, even now…over 500 years after its publication.

Called The Dream of Poliphilus in English, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is an arcane allegory in which the main protagonist, Poliphilo, pursues his love, Polia, through a dreamlike landscape. In the end, he is reconciled with her by the Fountain of Venus. Over the years, scholars and general readers have identified complex hidden messages and meanings within the text. Although it is structured like a novel, the work predates the European novel and is closer in genre to the Romance. It follows the conventions of courtly love and shares its rhapsodic style with Romantic Italian poetry.

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is written in a bizarre Latin-Italian that would have been strange even to readers at the time of its publication. The effect would have been similar to what it is like now to read Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon, which features the frequent capitalization, grammar and prose style of the 18th century or William T. Vollmann’s Argall: The True Story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith (2001) which is written in an even earlier Elizabethan prose. The text of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is full of words based on Latin and Greek roots because arcane writings were thought to lend legitimacy to Renaissance-era texts because it demonstrated classical thought. Remember how Alex Trebek used to pedantically correct the French pronunciation of his mostly American quiz show guests? He exaggerated his Quebecois pronunciation of French for the same reason Colonna sprinkled foreign phrases across his book. It makes them look smarter than they are. Hypnerotomachia also includes Arabic and Hebrew words, and Colonna would even invent entirely new words when real ones were unsuitable for his purposes. The book even contains bogus Egyptian hieroglyphs drawn from a fifth century text of dubious origin called Hieroglyphica. Whether Colonna knew the hieroglyphs were bogus or not is unknown but neither would be surprising. Colonna’s approach to other languages and even other writing systems seems to be “the more the merrier.” Some readers think he used foreign languages to ramp up the surreal atmosphere of the store: to approximate the strangeness of dreams.

James Joyce famously tried to do the same thing with 1939’s Finnegans Wake, which is a modernist quagmire of puns, made-up words, random foreign languages and an elusive plot. The Wake was a deliberate reaction to his previous novel, the wildly successful Ulysses, which followed a rogue’s gallery of characters across a single twenty-four hour span on June 16 1904, the day Joyce met the woman he would later marry, Nora Barnacle. The stylistic calisthenics of the novel were Joyce’s attempt to “reconstruct the nocturnal life.” Finnegans Wake ostensibly takes place over the course of a single night’s dream but the text is so confusing that even now, 75 years later, there is still no critical agreement on who the dreamer of the novel is. It is generally agreed that the novel’s text is not conveying a dream of a single dreamer but an attempt to convey the feeling of dreaming itself. There is plenty of textual evidence to suggest that Joyce wanted the reader to recognize their own dreams within the text. Part IV provides strong evidence, as when the narrator asks “You mean to see we have been hadding a sound night’s sleep?” (“see” means “say” and “hadding” means “having,” which is just one of the novel’s many departures from normal spelling in order to recreate the nonsensical surreal nature of dreaming. The same narrator later concludes that what has gone before has been “a long, very long, a dark, very dark [...] scarce endurable [...] night.” This is consistent with Joyce’s comments on the book. Public response to Finnegans Wake was almost universally negative based on the excerpts Joyce published in literary journals throughout the 1920s and early 30s. This rankled Joyce because he really did work hard on the novel. It’s not the tossed off work of a charlatan. The novel is hard to read but it rests on a foundation of consistent mythology and symbols.

I can't understand some of my critics, like (Ezra) Pound or (his patron) Miss Weaver, for instance. They say it's obscure. They compare it, of course, with Ulysses. But the action of Ulysses was chiefly during the daytime, and the action of my new work takes place chiefly at night. It's natural things should not be so clear at night, isn't it now?

Joyce pretended to be confused by the reception but he surely must have known the demands he was making of his readers. Finnegans Wake is one of the most difficult English language novels in the world. It has generated an enormous amount of literary criticism but it has never been widely read by the general public and it caused many of Joyce’s contemporaries to turn on him, most famously Ezra Pound and Joyce’s patron Harriet Weaver but even Joyce’s brother Stanislaus scolded him in a letter for “turning his back on the layman in order to write an incomprehensible night book.” There is a book club in California dedicated solely to reading Finnegans Wake. It took them 28 years to reach the end. They started in 1995 and finished in October 2023. That’s even longer than the 17 years it took Joyce to write the fucking thing. In 2019, the CBC wrote a profile on a Seattle man who is currently 6 years into a 17-year project of memorizing the entire novel.

It’s more fun to read about Finnegans Wake than it is to read it. Anthony Burgess (A Clockwork Orange) famously advocated for Finnegans Wake, calling it “a great comic vision, one of the few books of the world that can make us laugh aloud on nearly every page” but my favourite piece of writing on Finnegans Wake is Michael Chabon’s “What to Make of Finnegans Wake?” published in the New York Review of Books in 2012. Chabon begins by mentioning how long he’s been putting off reading Joyce’s final novel, having first worked his way through Joyce’s early poetry and his lone play, Exiles, his celebrated 1909 short story collection Dubliners (a masterpiece), 1912’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and 1922’s Ulysses. “After that,” Chabon writes, “I came up against the safety perimeter, beyond which there lurked, hulking, chimerical, gibbering to itself in an outlandish tongue, a frightening beast out of legend.” It’s a great read but, again, is a novel great if it’s more fun to read about it than actually read it?

I tried to read Finnegans Wake. The plot is simple, actually. The writing is dense and allusive and nearly impossible to follow. The story centres around a family who live in the Chapelizod neighbourhood of Dublin. (This is one of the many paradoxes of Joyce. He was one of the most cosmopolitan writers of his day, having lived in Zurich, Trieste, and Paris after leaving Ireland in his early 20s, never to return, but he wrote exclusively about Dublin.) The patriarch of the family is Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (referred to throughout as HCE…many early critics of the novel believed him to be the novel’s “dreamer” but this is no longer an accepted theory), his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle (referred to as ALP) and their children, sons Shem and Shaun and daughter Issy. HCE owns a small tavern and his family works with him there. When the novel begins, HCE is in the midst of being socially ostracized for a rumour that is never explained. He has also recently suffered a very bad fall.

The book begins like this: Riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

Okay. So Howth Castle is a historical building in Dublin. Its “Environs” are the city streets around it. But already we can see that Joyce is going to repeat the “HCE” acronym all over the novel. Howth Castle and Environs appears in the first sentence. A recurring phrase in the novel is “Here Comes Everybody,” which critics think was Joyce’s nod to the emergence of mass media because suddenly people were everywhere, on the radio, on the telly, on billboards, etc, but there was also a famous politician in Ireland in the 1880s named Hugh Childers who was nicknamed “Here Comes Everybody” for his great girth. Joyce writes that HCE is “man of hod, cement and edifices” and “like Haroun Childeric Eggeberth.”

The fall that HCE suffers is supposed to mirror the fall of man and Joyce’s uses the rich symbology of the river to show the cyclical nature of time (Chapter 8 in Finnegans Wake is comprised mostly of river names. Thousands of them.) Anna Livia Plurabelle is supposed to represent the eternal and universal female. For Joyce, the detritus of history washes past on a river of time, only to wash past us again. The novel begins and ends with the word “riverrun,” meaning the reader is supposed to return back to the beginning upon finishing the novel. It’s a circular narrative that doesn’t end, like Melville’s The Confidence-Man or Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music which contains a locked groove that plays the last minute of the record over and over again until the listener physically lifts the needle off the record.

The HCE example is just one of many recurring motifs in the book. Images repeat, the dream grows strangers, and the rumour about HCE mutates, eventually taking on gigantic proportions. The constant wordplay (puns, japes, jokes) and foreign languages can tire out even the most sympathetic reader. The novel is clearly a bridge between literature’s Modernist era (Virginia Woolf, Henry James, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway) and the postmodern era (Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, John Barth, Joseph McEllroy, Zadie Smith) but it’s mildly amusing that Joyce believed himself to be breaking down barriers and writing a new kind of novel when Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a similarly confounding novel full of strange symbols, made-up words, and foreign languages intended to mimic the strange language of dreams was published 440 years earlier. Joyce was unwittingly contributing to the cyclical nature of time simply by writing such a book. If Colonna’s approach to writing was “the more the merrier” perhaps the publication of Finnegans Wake attests to the old adage that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

What about the above-mentioned Hieroglyphica, the book Francesco Colonna used as a reference for his hieroglyphs? Is it bullshit or not? Well, the editions that Colonna would have had access to in late-fifteenth century Italy would not have contained exclusively authentic Egyptian hieroglyphs. But here is where it gets confusing. The original Hieroglyphica would not have been completely accurate either (scholarly consensus is roughly 50% of the original edition was accurate). This is not just the fault of the many translations the work went through. The author of Hieroglyphica is believed to be a 5th century Greek author named Horapollo. Horapollo is mentioned in The Suda (a 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world) as one of the last leaders of an Egyptian priesthood at a school in Menouthis, near Alexandria, during the reign of Zeno (474–491). This means that even though Horapollo spoke and wrote Greek as a first language, he wrote Hieroglyphica - a book explaining Egyptian hieroglyphs…in Egyptian Coptic. We know this to be true because a Greek translation of Hieroglyphica by a figure only as Philippus existed in Greece in the 5th century.

In other words, the first time Hieroglyphica was published in Horapollo’s first language (Greek) in his home country (Greece), it was already a second-hand document because it was a translation from the original. Muddying the waters further, there are two entries in The Suda (an enormous encyclopedia with over 30,000 entries) under the name Horapollo. The elder Horapollo is the author of Hieroglyphica, the other is the grandson of the author. According to Anthony T. Grafton’s 1993 foreword to The Hieroglyphics of Horapollo, both the younger and elder Horapollo were students of both the Egyptian tradition and Greek philosophy, but the lost Egyptian learning they tried to cobble together and reconstruct were “a mix of the genuine and spurious.” This is how we know that the very first edition of Hieroglyphica contained 50% correct hieroglyphs and 50% erroneous ones. However, because no copies of the very first edition survive, the only source we have for the assumption that the Philippus translation was from the Egyptian Coptic into 5th century Greek is Philippus himself. Naturally, nothing is known about him. If he wrote original works or published other translations, they did not survive and no references to other works by Philippus can be found in surviving contemporaneous works.

Knowing what we know about anonymous and pseudonymous authors, the Philippus “translation” could very well have been an invention of Horappolo himself. After all, what better way to shield himself from criticism that the hieroglyphs were inauthentic? He could simply claim that the translation was faulty and that he made it very clear in the original text that half of the 189 hieroglyphs in the text were probably erroneous.

The original text of the Hieroglyphica consists of two books, containing a total of 189 explanations of Egyptian hieroglyphs. The text was immediately obscure. There are no instances of it being cited for the first 900 years after its publication (this has led more than a few commentators to pronounce the work a fifteenth century forgery…but it can’t be if half the text is correct). Philippus’ Greek translation was rediscovered in 1419 on the island of Andros, and was taken to Florence by Cristoforo Buondelmonti (c. 1385 – c. 1430), an Italian Franciscan priest and traveler. The first printed edition of the Philippus translation appeared in 1505 and was translated into Latin in 1517 by Filippo Fasanini, initiating a long sequence of editions and translations.

From the 18th century, the book’s authenticity was called into question, but modern Egyptology regards at least the first book as based on real knowledge of hieroglyphs, although confused, and with baroque symbolism and theological speculation, and the book may well originate with the latest remnants of the Egyptian priesthood of the 5th century. This is consistent with the few known facts about Horapollo’s life. Though a very large proportion of the statements in the book seem absurd and cannot be accounted for by logic, there is ample evidence in both books that the tradition of the values of the hieroglyphic signs was not yet extinct in the days of their original author. In other words, Egyptian hieroglyphs were still being taught in Egypt in the fifth century, more than 400 years after Cleopatra (the last Egyptian pharaoh) died. By the end of the 15th century, Hieroglyphicaimmensely popular among humanists and was once again translated into Latin by Giorgio Valla (1447-1500), an Italian academic, mathematician, and translator. The Valla translation is most likely the version that Colonna borrowed from when inserting hieroglyphs into Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.

It is no accident that the pedigree of Hieroglyphica was called into question in the 18th century. Literary forgeries exploded in popularity across Europe in the 1700s but the problem was particularly bad in England. Anonymous authors were rife across the island’s literary scene in the 1700s. It’s almost as if something in the eighteenth-century English character gave rise to modesty of authorship. It’s ironic that the authority with which the classic literature of early modern England was written - the flowery pronouncements of its pseudonymous producers read more like eternal truths than emergent ones - did not extend to a zeal for attribution or recognition.

The finest satirist in the English language, Jonathan Swift, published his work under the noms de plume Lemuel Gulliver, Isaac Bickerstaff, M. B. Drapier or entirely anonymously. The identity of the writer behind the popular Letters of Junius (1772) has never been satisfactorily verified and the mimicry of Thomas Chatterton was so skillful that he was able to successfully pass off his work as that of an imaginary 15th-century poet named Thomas Rowley. Chatterton’s ruse was exposed by Horace Walpole and he killed himself with arsenic soon afterward. He was only seventeen when he died. He’d started writing poetry that mimicked medieval verse at the age of eleven. Had Chatterton not died, who knows what he would have gone on to write. The below painting is called The Death of Chatterton by Henry Willis, painted in 1856.

Shakespeare forgeries were a major public controversy in 1790s London, when author and engraver Samuel Ireland announced the “discovery” of a treasure-trove of Shakespearean manuscripts by his son William Henry Ireland. Among them were the manuscripts of four plays, two of them previously unknown. The forgeries were unwittingly given legitimacy when such respected literary figures as James Boswell (biographer of Samuel Johnson) and poet laureate Henry James Pye mistakenly pronounced them genuine, as did many other antiquarian experts.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the leading theatre manager of his day, suspected something fishy but went along with the charade, going so far as to stage one of the “rediscovered” plays titled Vortigern. But Sheridan’s stable of actors were intimately familiar with the language and cadence of authentic Shakespeare and were unwilling to play along with what they knew to be a forgery, so they deliberately sabotaged Vortigern on opening night by giving terrible performances. So mercilessly did they mock Vortigern and so viciously did the leading Shakespeare scholar of the day, Edmond Malone, pronounce the play a forgery that William Henry Ireland eventually confessed to the fraud and left London in disgrace. His father, meanwhile, insisted until his death that the discoveries were real. He had more to lose. The fakery had been his idea to begin with.

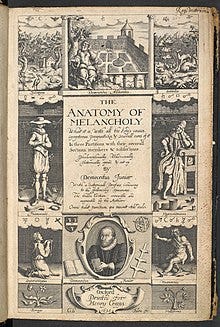

Laurence Stern’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759) borrowed many passages and sometimes whole pages from Robert Burton’s sprawling masterwork The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Burton’s Anatomy was initially published under the name Democritus Junior, and proved a highly influential model for Swift, Sterne and an entire generation of English authors. More than any other post-Renaissance English text, The Anatomy of Melancholy is a sui generis. As toweringly impressive as William Blake’s artistic achievements were and are, no single work of Blake’s can rightly be described as “in a class by itself” because his prophetic works are interrelated and draw on Blake’s own complex personal mythology. No single work of William Blake’s stands alone, even if each work is that of a genius. Blake’s poetic texts depend for their cumulative power, context and coherence on each other, whereas Burton never published anything else remotely like The Anatomy in his lifetime. Though he published plays, nothing else he wrote comes close to the encyclopedic and labyrinthine scope of his magnum opus. Presented as a medical textbook on the subject of melancholia, the book is as much a work of literature and the imagination as a scientific work. In addition to the author’s techniques, the Anatomy’s vast breadth - addressing such random topics as digestion, goblins, the geography of America, and others - make it a valuable contribution to multiple disciplines. It was greatly admired in its day and still read now.

The last example of a mysterious work I will give is the friar John Burton’s confounding work of urban sociology, psychogeography, and social history, The Distance to Here, which has entertained and perplexed its admirers since its 1775 publication. The Distance to Here provides a detailed history of the city of London written not in a linear format but arranged around seemingly random topics such as the senses (“sight,” “sound,” “smell,” “taste” and “touch”), spectacle, public execution, light, space, ghosts, public works, the plague, prostitution, graffiti, the weather, the justice system, the Thames, the black market, murder, alcohol, warfare, and many other wonderfully obscure topics. The true identity of its author has never been confirmed but that’s not the biggest mystery surrounding the text.

The Distance to Here features a baffling forty page section near the middle that provides a detailed history of a set of a London neighbourhood that does not exist and never did, and whose apocryphal status has perplexed the book’s critics and advocates for 400 years. The accuracy of the other sections of the work are beyond repute, which makes the made-up section even more confusing. Was Burton trying to make a statement about the limits of authorial authority or was he just trying to fuck with people? The first critic to notice this eerie section was the ever-alert Horace Walpole but instead of making the tempting claim that the inaccuracy of the section discredited all others, Walpole warned his readers otherwise:

It would be tempting to claim the author of The Distance to Here a charlatan and a fabulist, but 860 of its 900 pages are of such quality that these perplexing forty pages that purport to tell the history of a non-existent neighbourhood in our fair city must have justification that goes beyond my apprehension. The writer who produced those 860 pages is not a charlatan but an artist of the very highest order. I shall therefore reserve judgment on the contested passages until such time as their purpose is made more clear.

The go-to postmodern trick is the book within a book. The prestigious example is Nabokov’s Pale Fire, a novel presented as a 999-line poem titled Pale Fire written by the fictional poet John Shade. The book features criticism by Shade’s neighbour and academic colleague, Charles Kinbote, but Kinbote barely concerns himself with the poem. His so-called “commentary” is full of envious invective, personal concerns, and random thoughts about other topics. (This wonderful randomness is a major characteristic of every book about a book or book within a book.)

Thomas Williams’ The Hair of Harold Roux is that rare example of an unabashedly literary work that enjoyed critical praise and bestseller status (it shared the 1975 National Book Award with Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers). Harold Roux takes place over a long weekend in the life of Aaron Benham, a clinically depressed literature professor at a New Hampshire college who has taken a leave of absence to write a novel called The Hair of Harold Roux. (This is unsurprising. In recent years, most books within books share their title with the book they are in. Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding being a recent example.) Williams punctuates the primary plot with flashbacks to a long fairy tale that Aaron tells to his children and Aaron’s experiences in college following World War II.

Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves employs the text-within-a-text concept but updated for our screen-filled era. The document in question is a mysterious film (released by The Weinstein Company) titled The Navidson Record, consisting of home-recorded video footage of Will Navidson’s house where he lives with his girlfriend Karen Green and their two children, Chad and Daisy. Will begins documenting events soon after accidentally stumbling across an architectural anomaly: the inside of his house is bigger than the outside. Soon after, a dark hallway appears in his living room which leads into a strange, maze-like complex. Navidson hires professional explorers to map out the maze, some of whom never return. The Navidson Record is full of academic footnotes placed there by an unknown party. The sheer number of footnotes, and their tonal orientation, are clearly a satire of academia.

Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project is a philosophical work featuring an enormous collection of writings on the city life of Paris in the 19th century. It is especially concerned with Paris’ iron-and-glass covered “arcades” (known in French as the passages couverts de Paris). I happen to think it’s literary significance has been grossly overstated because its reputation rests mainly on what it could have been and not what it is (scholars believe it would have gone on to become one of the twentieth century’s greatest texts of cultural criticism if not for Benjamin’s mysterious and sudden death at the French-Spanish border in 1940). I will reserve final judgement but I feel it’s unfair to judge a book by what it might have become.

My fascination with books of this ilk has led me to spend most of the past year working on a new book. I’m trying to produce something that could evoke in readers the same excitement I felt when I first read House of Leaves or The Hair of Harold Roux or Anatomy of Melancholy. It’s called To the Glum Alumni and it’s about a professor who fears she will be exposed as a fraud for having stolen her PhD thesis. She is working on a long commentary of John Burton’s The Distance to Here that she hopes will legitimize her in the eyes of her peers and also grant her tenure. But because The Distance to Here is so obscure, she starts inventing things about it in order to have more material to write. Pretty soon her lie becomes uncontrollable and the shit hits the fan. I’ve always wanted to write a campus novel because I’m a huge fan of the subgenre. The Secret History is one of my favourite novels and I love Stoner, The Name of the World, The Rule of Four, Hearts in Atlantis, White Noise, The Marriage Plot and Lucky Jim. Here’s hoping I hit my mark. And here’s hoping it doesn’t take 14 years again

.